Miguel

In which a student does not live out his dream of going to Japan

Miguel and his mom came into my office a few days before the school year started and with some embarrassment, at least on the mom’s part, pulled out a transcript showing his grades from his previous school, where he had ostensibly attended 9th grade. He’d failed just about everything, which is why, the mom explained, they were excited to be transferring into our school. A fresh start. She looked at Miguel. He nodded with great sincerity.

He was a handsome, olive-skinned kid with Venice Beach bracelets and a hint of a goatee. The transcript said he was 14 but passing him on the street I would have taken him for 18 or 19, maybe a bar back at one of the restaurants downtown, earning good money and hitting on tourists.

I was 33 myself, at the end of a good run as a teacher and coach at that school, a small charter in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and now somehow had become dean. I scratched some numbers on a legal pad for Miguel and his mom and showed him how if he really applied himself and took some summer classes there was a chance he could pick up enough credits to graduate on time, but that he’d be classified as a freshman for the time being. Miguel didn’t seem to mind. We set up his schedule and he thanked me, shook my hand and held the door for his mom on their way out.

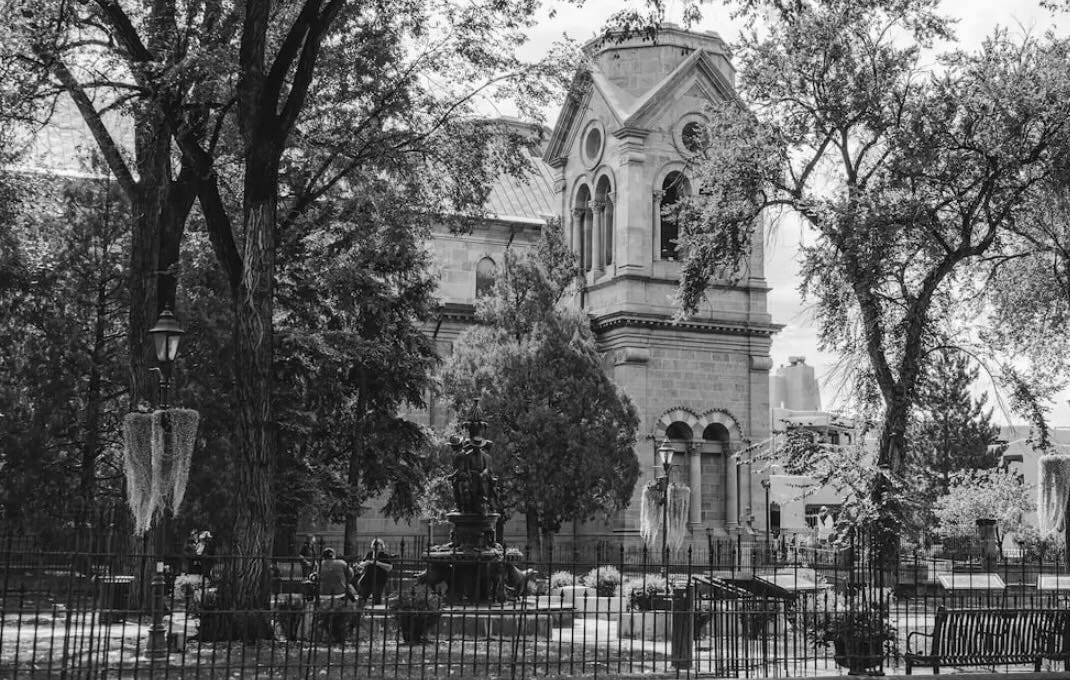

Within a few weeks of school starting it was clear Miguel had no intention of applying himself to anything related to school at all. He oozed with charisma and loved life was unwilling to make the bargain of trading in having a great fucken time in high school for some hazy promise of a college degree or good job in the future. He knew his way around a guitar and liked smoking good weed and flirting with girls, who were happy to flirt back. He seemed to have decent academic skills and now and then would get interested in a book, though nothing required for any of his classes. When he got tired of teachers telling him what to do or curious about what was happening in the world beyond the school walls, he would walk out of the building with his skateboard, and, as far as we could tell, hop one of Santa Fe’s very occasional city busses to the downtown Plaza, where young people of his mindset and disposition would gather, often in a little park beside the Cathedral, of all places, to pursue their education in more informal ways, smoking up and playing banged up guitars and telling stories.

As dean it was my responsibility to figure out what to do whenever Miguel left campus. The only thing I could come up with was to call his mom, who, I learned, was raising him on her own. She loved Miguel deeply. She also treated him essentially as an adult, more like a roommate than a son. When I called she would answer the phone from her job, sigh, ask what it was this time, and then wonder about the decisions being made by this young man with whom she shared her life. She always apologized for the trouble he was causing, but it was clear she had even less idea than me how to force him to stay in school.

I didn’t have much else to throw at the problem. It was my first year in any sort of school leadership role, and the fiercest punishment I could imagine was suspension, which didn’t seem a great option for a kid who loved any excuse to miss a day of school. Assigning him a detention was equally toothless: he would have skipped it, which would have lead to a suspension. But I had to do something, so I would call him into my office after his ditch days and try to talk things through.

Most of the kids who came through my office that year were miserable and needed a therapist or a puppy or a year off of school more than a stern talking-to from an inexperienced dean, but Miguel was different. He would come in and greet me and drop into the chair and ask me how I was doing. I would spend a few moments going through the motions of trying to convince him of the importance of getting a diploma, etc., but both of us knew he gave a rat’s ass about all that, and we’d end up talking about much more interesting topics. He was a good conversationalist and in no particular rush to get out of my office and back to class, unless it was lunch time, so we had some lengthy conversations. Despite his oft-stated opinion that I had one of the crappiest jobs on the planet, he treated me with respect, and was interested to learn about places I had lived and traveled.

In one conversation he asked me if I had read the book, The Secret, which I gathered another kid had given him during one of his afternoons downtown. I did not know the book, so he described with great enthusiasm how it provides irrefutable proof that the way to get where you want to go in life is not by going to school and college and working hard, but by mentally manifesting the life you want to live—the house, the cars, the relationship, the travel—and letting it arrive. By all appearances, he was determined to live by this philosophy.

Despite his oft-stated opinion that I had one of the crappiest jobs on the planet, he treated me with a sort of respect, and was interested to learn about places I had lived and traveled.

The year rolled on, with Miguel coming and going as he pleased. Now and then he would turn in an assignment, and when he was dating someone he’d tend to stay on campus a bit more, but it seemed he had no intention of actually earning high school credits until one day in the late spring, when he surprised me by showing up for the senior class graduation at an auditorium downtown. As everyone took photos after the ceremony, he approached me to share that he had been pretty moved by the ceremony.

I cocked my head. “No, you weren’t.”

He insisted he was, and he was being genuine. For some reason, the pomp and circumstance had touched him. “I’m going to graduate,” he told me. “I want my mom to see me up on that stage.”

So until then he’d been planning to not graduate?

“Honestly, Mr. Biderman,” he confessed, “I only came to your school because I heard you had a trip to Japan”—which was true, we offered Japanese and did take a group of students to Japan every other year. I thought back to that first day in my office, and recalled that he had in fact asked about Japanese, and eagerly selected it as his language option. He shared now that he loved anime, and that his plan all along had been to get on the school trip, ditch the students and teachers on a street corner in Tokyo, and live a few years in Japan, apparently unaware of or unconcerned by such trivialities as acquiring visas, purchasing food, sleeping indoors, etc.

But now, he said, he wasn’t going to ditch the trip. He was going to graduate. And he meant it.

A few weeks later, on the last day of school, the worst day of the year for school administrators, when the kids who most hate you can finally exact their revenge with shaving cream and water balloons and high powered squirt guns, knowing that we adults are disarmed and defeated by then, unable to suspend the kids as there’s no school the next day, too damn tired to call in their parents for another conference—I stood outside my office, watching the kids stream out of the room toward freedom, feeling a bit like the captain on the Titanic, trying to hold my head up nobly, when Miguel sauntered up with a younger buddy. They wished me a good summer, popped two water balloons over my head, and sprinted out of the building.

By that point I had already informed the school that I was not going to return as dean of students. It had been an unhappy experience, nine months of me enforcing rules I’d hated as a kid, telling young people things I’d swore I’d never tell them, nothing like the delightful years I’d spent teaching at that school. No self-respecting dean of students would tolerate a water balloon getting popped over his head, and in front of other students and staff no less, but as much as I knew I should have chased after Miguel, brought him to justice, restored order and dignity to the world and my profession, I could only wipe the water from my eyes, and laugh.

And thank God I did. I saw Miguel for the last time a few weeks later, in downtown Santa Fe, on a gorgeous summer day. He was walking west on San Francisco Street, with the Cathedral behind him, in the company of a couple of pretty girls. He wore a cast on one arm, had broken it skateboarding, I imagined. I was with my wife, and Miguel introduced himself and smiled charmingly at her, then introduced us to his friends. We were genuinely happy to see each other. I told my wife about the water balloon and how he was going to Japan someday, and Miguel smiled, and then he extended a hand. I took it, thinking we were going to shake, but he pulled me into a hug, his cast pressing gently on my back, and walked off.

That night, caravanning to a party out the outskirts of town, the car in which he was riding plowed head on into a drunk driver coming the other direction. Miguel and three other kids were killed. A colleague called me in the morning to break the news. But I just saw him, was all I could say. I just saw him, yesterday afternoon.

I like your writing, Seth. I read Teacher Man (Frank McCourt) last year and I realized I love reading teacher memoir. I'll continue reading as this substack. Thanks for storytelling

Riveting, heartbreaking.