Six adults sit in silence around a heavy black table when I enter the conference room.

“Afternoon,” I say.

A muted response.

The conference room is sparse: Stained drop ceilings and unadorned cinderblock walls painted some forgettable color. Outside the windows, the afternoon skies are leaden, the light grey.

For some reason the one thing this room has in abundance is office chairs, all adjusted to different heights and spine angles, and I have to play a brief game of chair Tetris to negotiate a spot at the table. I open my laptop, not because I have prepared for the meeting, but because that’s what principals do when they come into a meeting, and on cue the woman on my left, our Director of Special Education, or perhaps her title is Director of Special Services, or maybe Director of Student Services, passes out to each of us a neatly stapled 27 page document, the Individualized Education Plan for an 11-year-old child named Billy.

This unpoetic document must be reviewed once a year, which is why we’ve assembled, we seven silent adults—Billy’s mother, who glares at me; Billy’s father, who glares at Billy’s mother; Billy’s English teacher, his case manager, a contractor who is an occupational therapist, the Director and me—only after we’ve all stated our names and titles do I realize we are actually nine adults: From the unassuming landline phone in the middle of the table comes the voice of a woman who introduces herself as a lawyer for Billy’s family, and—right back at you—from the speaker of the Director’s iPhone, a woman who introduces herself as legal counsel for the school.

I settle into my chair.

Overhead, the clock ticks.

The Director plunges immediately into the details of Billy’s plan, because that’s all an Individualized Education Plan is, details, all details, Billy divided into 20 or 30 discrete, measurable academic skills, like “Billy will be able to correctly identify the main idea of a paragraph 60% of the time,” or “Billy will correctly solve a two-step equation on 4 out of 5 attempts.” If you read closely, between the lines, if you squint and give a few Tinkerbell claps, you can sometimes find a bit of a description of the actual child in an IEP, a phrase or two that serves to remind that this document is dealing with a human being, a slight nod to the incontrovertible but legally irrelevant fact that it’s a miracle Billy was born at all, that the odds of his particular parents meeting, and of that particular sperm of his father’s swimming its way to that particular egg of his mother’s, and then successfully implanting in her uterus, and then him being carried to term and successfully brought into the world, are impossibly low. In IEP terms: “Billy’s father’s sperm will successfully fertilize Billy’s mother’s ovule .000001% of the time.”

In our school of about 360 kids there are 100 or so who have some sort of tailored plan like this, some longer, some shorter, each a legally binding document stipulating in precise terms very specific tasks that we adults must do to meet the particular goals of that particular child, which may be as simple as allowing them to chew gum (a proven remedy to Attention Deficit Disorder, as it turns out) or as complex as creating an entirely alternative curriculum, with adjusted grading scales and modified assignments. Each of these tasks—and there are thousands of them-- must be documented and monitored daily, which is the job of our Director of Special Education, who as a former lawyer with the work ethic of corporate Japan has proven very much up to the task, though clearly something has gone sideways in Billy’s case, if the lawyers are here.

I can hear the family’s lawyer clacking on her keyboard through the speakerphone, as the Director reads the plan. I wonder what she is typing. I wonder if I should be typing something too. I wonder where she is, this lawyer, if she’s in a lovely office suite overlooking the National Mall, a Nespresso machine whirring gently on the midcentury side bar behind her, and then I wonder if it’s too late for me to go to law school, how awkward it would be for me to be that one middle-aged student who’s always raising his hand during the lectures, and who can’t go out for drinks after class because he’s got a family at home.

Billy’s mother clears her throat.

I steal a glance at the Director’s copy of the document. We’re on page two. I flip the page.

She has donned reading glasses, Billy’s mother, and she says she has a question, though it is clear it is not quite a question. She would like to know why Billy’s seat in his science class is not in the front of the room. Right here it says in black and white that Billy will be given preferential seating in the room in all of his classes. Does this not include science?

The Director replies, evenly, that every teacher has been given the plan, and been instructed to follow it.

She turns to me. Billy’s mother removes her reading glasses and steels her gaze on me, and then the speakerphone lawyer stops her keyboard clacking and everyone in the damn room looks at me, Mr. Biderman, the Supreme Master of Everything That Teachers Do in the Middle School.

I swallow.

Here’s the truth of the matter, which I can confess now, with only a slight fear that I will be sued, retroactively, for educational negligence: I have no idea where the fuck Billy sits in his science class. I have no idea if our science teacher, whom we hired midyear out of a pool of exactly one qualified candidate, and has been barely hanging on, has had time to read Billy’s IEP, and even knew to give him a seat in the front of the room.

But that’s now what you say, when you’re a principal. I need something else. Something not quite true but not legally a lie.

…everyone in the damn room looks at me, Mr. Biderman, the Supreme Master of Everything That Teachers Do in the Middle School.

As whenever I consider doing something not quite ethical, my jaw clenches, my pits sweat, and my mind whips me through a psychological and emotional journey of key moments of immorality, beginning with stealing a toy from the shelf at my preschool, a tiny wooden house that I secreted into my pocket and kept in my bedroom, and would stare at from my bed every night with a mix of joy and guilt; to my middle school friends and I shoplifting a candy bar from Osco Drugs on the way to Wednesday afternoon confirmation class at Hebrew school, where my mother, as it happened, was set to guest teach our class a lesson on ethics. A whirl of all my life’s transgressions clatters through my poor body, leaving me with no clarity except how much I really do not want to be a principal right now.

I glance out the window. Not for the last time in my career I pray for an explosion outside the building, one that does not hurt anyone or cause major damage but forces an immediate evacuation.

It does not happen.

They are waiting.

I state, quietly, mumbling a bit around the edges, that although I cannot actually confirm where Billy sits in science class on every given day, as the seating arrangement is often adjusted to maximize student learning, all teachers review all IEPs, of course, and I know the science teacher has been particularly attuned to Billy, which is true, teacher has come by my office a couple times to ask what in God’s name he’s supposed to do with Billy.

Who, by the way, we all love. He’s a sweet kid, perceptive and curious and lovely to chat with. If only this meeting were about that, about who Billy is, how we can help him become who he wants to be, about how we can support Billy’s mother and father, who must be terrified that their son will almost certainly outlive them but may never develop the skills to live independently. What Billy needs, what this family needs, is nowhere on this plan, arguably nowhere in this building, maybe not in any school building.

I don’t say any of that.

The mother is nodding slowly. She would like to make an observation.

As it happens, she says, she knows exactly where her child sits in science class, because although Billy himself is not verbal enough to report out, she has sent Billy’s older sister, an 8th grader, to ascertain the situation. In fact, just this Wednesday the sister went into the science room, the mother tells us, and saw her brother sitting in the last row, doing absolutely nothing.

Again, all eyes in the room turn to me, Mr. Biderman, Middle School Principal. Twenty years in education, twenty years of climbing up playground backstops to rescue Jonathan from bees, calling Joey at home at night to remind him to read, crying over the death of Isaiah, missing weddings and family dinners and life to grade papers—none of it matters, not a minute of it.

I keep my mouth shut.

The only person who seems not infuriated or embarrassed at this moment, oddly enough, is Billy’s father. He gives me the slightest of nods, as if to say, “we men are a sorry lot, indeed.”

Mercifully, skillfully, the Director intervenes. “We’ll make sure that is remedied,” she says. The speakerphone lawyer clacks. The mother puts on her glasses and turns her attention back to the IEP, preparing to levy her next attack.

The IEP meeting slogs on, and though the pages on the document turn and the clock ticks overhead, it does not seem like we are advancing. I will be in this IEP meeting forever, Prometheus-bound to this office chair, facing for eternity the wrath of Billy’s mother, the clacking of the invisible lawyer, page upon page upon page of tasks and modifications and goals. The tenth circle of hell.

But it does come to an end, of course, we get to the part of the meeting where the lawyers start negotiating and the school ends up buying its way out of a lawsuit by offering the magic cure-all to all special education offenses, “compensatory services,” which in regular language means the school will foot the bill—at over $100 an hour—for private tutoring so Billy can make up whatever he’s missed.

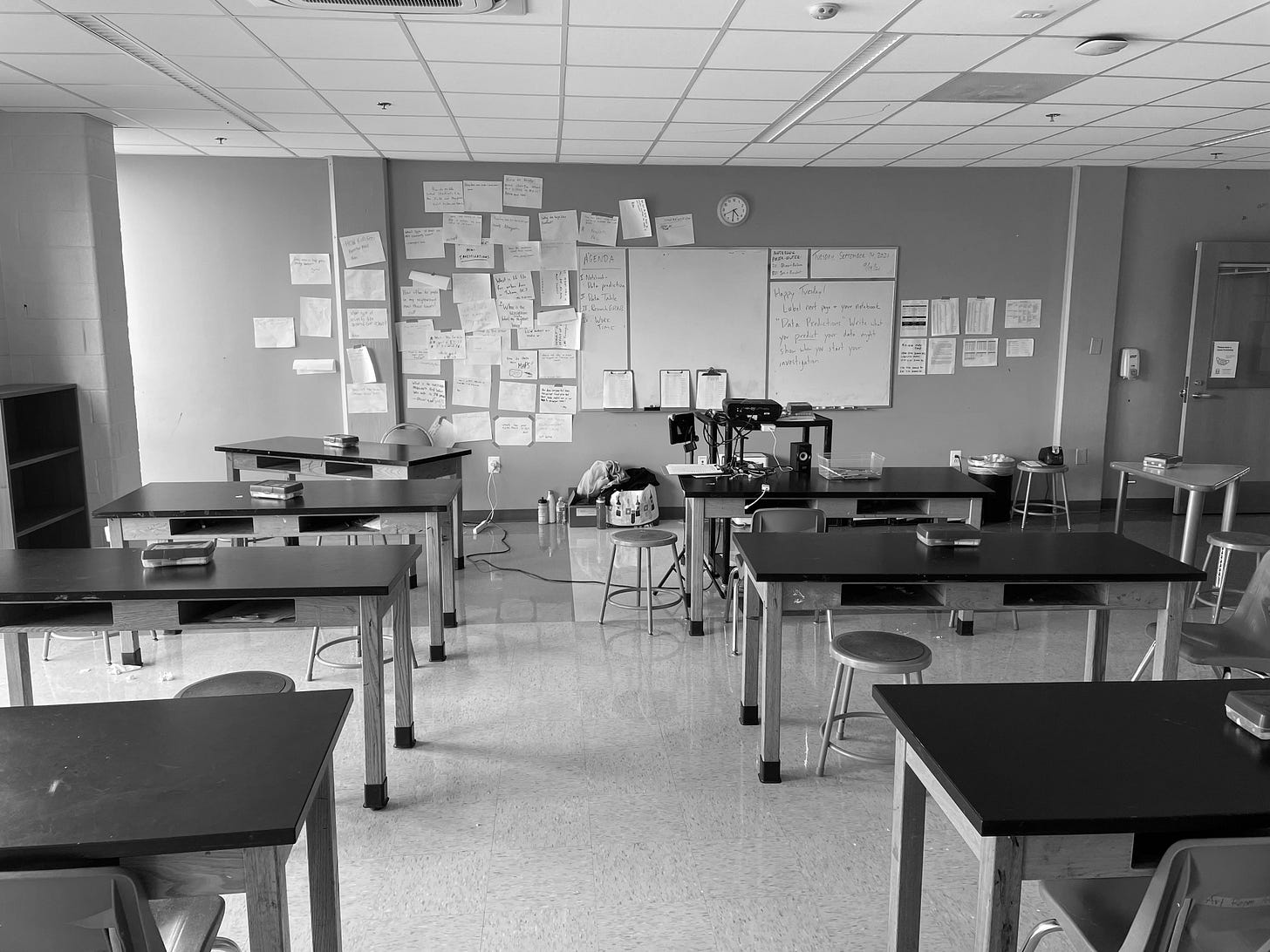

It is determined that Billy is owed hundreds of hours to compensate for all the hours he spent in the wrong seat in the science room, among other offenses, and so for the remainder of the school year is entitled to receive two hours of one-on-one tutoring daily. Since it cannot happen during the school day—which would mean excluding him from his peers, which his IEP does not permit—the tutoring must happen after school, when all the other students get to fly out of the building to eat Takis and play soccer and Legos and video games. For the rest of the year, as I walk down the hall at the end of the day, I pass by the classroom where Billy is given his tutoring. He sits at his desk, the only child in the room, a patient tutor standing before him, trying to draw his attention to the words on the board, urging him to focus just a few minutes more. And every afternoon Billy looks at me as I pass, eyebrows raised, eyes wide, as if to ask, What did I do wrong, Mr. Biderman? What did I do?

Really good article. Special ed and IEPs always seems to miss the mark for me. But then I don’t have much experience with it. I like a more wholistic approach to children

Excellent description of a difficult meeting over a convoluted process. Helps me understand why you had to leave this job for more fulfilling projects.